I’ve worked in education technology (#EdTech) for many years now and over the last 7 years I’ve co-founded and run a successful company (Airhead Education) delivering a web desktop to schools (Airhead). We won a Bett award for ‘Innovation in ICT’ in 2015 and achieved it without investment from any external source. We’re debt-free and we’ve made a profit in every year of operation. No, we’re not Google yet but we’re making our mark in the education sector and we continue to listen and grow. It’s certainly not been easy, but it has been a lot of fun and as we start 2017, I’ve been reflecting on a few of my lessons learned.

I’ve seen technology products and services designed for education come and go (and usually turn up again, reinvented). Often I’ve seen the merit in the idea but the execution has been poor. Occasionally, both the idea and the execution have appeared to be flawed. The thing is, I don’t have an issue with either scenario. Ideas don’t just spring into life fully formed; they need to be shaped in the fire of trial, error and reflection. And of course the same applies to the execution of ideas in the form of products and services. The process of releasing, reviewing and revising is a basic principle underpinning continuous improvement. And I’m not even perturbed if individuals without education experience try their hand at EdTech. Sometimes the education crowd can’t see the wood for the trees. But there’s one thing you must do: survive long enough to learn the lessons you need to learn in order to build a successful business.

So if you’re going to invest your time, energy and creativity in developing technology for the education sector, you should be sensitive to the characteristics of the technology and education markets and what they mean for your business. For me, there are three particular EdTech business challenges:

-

- Rapid lifecycles – The pace of change in technology is rapid and and the lifecycle of most technologies is therefore short. Whether it’s software, hardware or the services that support them, rapid evolution of technology means a requirement to make changes just to stay functional and relevant, let alone to evolve with your customers’ needs. Developing, delivering, maintaining and scaling products and services is a costly endeavour which requires unerring financial and technological vigilance.

- Tight budgets – The majority of educational establishments are under constant budgetary pressure and, rightly, there is a tension between competing requirements for investment. Educational establishments should not be taking excessive risks with the deployment of technology because they simply cannot afford to squander their budget. The consequence of this is an ever higher bar for the effectiveness of education technology vershe price paid.

- Risk Aversion – Education establishments are intrinsically risk averse for a variety of reasons. Limited budget is one of those reasons but so too is the price of failure beyond just money. Organisational failure in an educational establishment ultimately hits the learner and so an ‘if it ain’t broke don’t fix it’ culture often emerges to protect the learner from excessive educational experimentation, including with technology.

So let’s be clear about what this means for the prospective EdTech entrepreneur:

- Deep pockets – You’re going to need deep pockets in order to get your business off the ground and keep it running when technology is changing apace. You will need to factor in the cost of ongoing technological development because without it, you run the risk of becoming irrelevant just as you’re gaining traction in your market.

- Realistic assumptions – Take a long hard look at your business plan in terms of market size, adoption rate and price point. Make sure that enough customers will actually pay the price you need them to pay in order to survive. Be pessimistic and enjoy a nice surprise. There’s no point in creating something that users love but which they don’t value enough to buy.

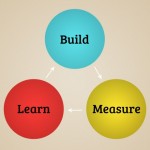

- Solid evidence – Test your product or service in MVP form (Minimum Viable Product) from the beginning and never stop soliciting opinions and analytics about its performance in order to create an evidence base for the efficacy of your creation. Whilst you may think you know how to solve a relevant problem, ultimately your customers need to agree with you and be prepared to recommend you.

Yes, I’ve learned a lot of lessons in the course of co-founding Airhead Education and no doubt there are many more to come. The truth is that I love what I’m doing and so it’s easy to get up in the morning and consistently spend time working out how to make Airhead better. As long as I can say that, I have the most important ingredient for success. Good luck in 2017!