In my previous post of this series I looked at the first and most important part of technology provision in schools: access. Without access, none of the potential learning associated with technology will take place. My conclusion was that although not all technology is or can be mobile, when constructing their technology strategy, school leaders should assume personally owned, mobile technology is the answer unless it clearly isn’t. They should assume this because the data demonstrates that mobile technology adoption is rapidly increasing because it offers a consistent, personal experience and availability at the point of need. Ask any mobile ‘phone owner. This leads to high utilisation and more opportunities for learning. These are important attributes in successfully embedding technology within new pedagogies and curricula as well as for extending learning beyond the school into informal and social environments.

The second part of my blog on school technology strategy is the ‘doing’ or ‘action’ part. This means schools’ core mission. This could be something like: “To provide the opportunity for all students to learn and strive for excellence.” [taken from Washington Elementary School’s web site]. The emphasis here is on learning, not technology. Technology is simply a tool and/or the subject of learning. For the purposes of this blog post, I will not explore technology as a subject, but rather I will focus on it as a tool. In this context, technology might:

- Qualitatively enrich or enhance learning and/or teaching

- Improve efficiency thereby releasing more time for learning and/or teaching

In developing a technology strategy for schools, school leaders must explore a range of options in both these categories in order to decide how they invest their budget. This means addressing two challenges:

- Prioritise investment of the technology budget to optimise learning

- Achieve best value through procurement efficiency and technical effectiveness

These two very simple steps hide a great deal of complexity but in separating them out, we begin to see where school leaders should lead and where they should follow. That is to say, school leaders are expected to have an opinion about how they wish to prioritise their resources to optimise learning outcomes in their organisations. That’s their job. It’s not (necessarily) their job to work out how technology can or will do this and then to procure and implement appropriate solutions. That’s probably best left to educational technology experts. There is a twofold and thorny problem here which may be characterised as “the blind leading the blind” or “the one eyed man is king in the land of the blind.” One face of the problem is school leaders who were not raised as digital natives and for whom technology is at best opaque and at worst an issue rather than an opportunity. The other face of the problem is that the so called ‘experts’ who tend to be either well meaning amateurs or individuals with vested interests. This is an unholy alliance in which neither party has much of an incentive to challenge the other.

So to whom should school leaders be listening when it comes to translating their organisational learning aspirations into learning outcomes through technology? Out of 28,000 teachers who qualified in 2010, just three individuals had a computer-related degree. Teachers are experts in learning and teaching, not technology strategy. Network Managers and ICT Technicians have a very clear vested interest in maintaining or expanding their roles rather than seeking out the most effective technology solutions. If it’s not them, then perhaps it’s a trusted partner organisation or a technically minded Governor. In my experience of the former, companies will sell what they have and a lack of competition leads to complacency. With regard to the latter, it’s rare to find Governors who understand and are sympathetic to technology in the context of education as their experience is usually derived from the corporate space. I’m not trying to discredit the positive motivation of any of these individuals. I know their hearts are generally in the right place. Nevertheless, in an average secondary school an annual technology budget is in excess of a quarter of a million pounds and good value means more learning. It is not something to treat lightly.

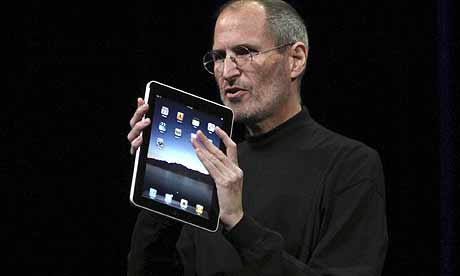

So my contention is that there’s very often a gaping hole where one would hope and expect to see an experienced education technology strategist without a vested interest. Bectatried to fill this space for schools in the UK and certainly they provided much needed advice, guidance and some procurement efficiency whilst they existed. However, they also fell into the trap of technology for technology’s sake. For example, some of their procurement frameworks for school products and services were so detailed that they drove unnecessary product and service complexity in the market. Complex products don’t get used unless they add real value. This is exactly the situation for many MLE and VLE products which languish in schools, receiving minimal usage and simply ticking the ICT box. Steve Jobs understood this well. Technology is only good if it’s used. Of course Local Authorities and other organisations such as NAACE and BESA have tried to plug the hole in various ways and there’s no doubt they do good work. The issue I see is that their impact is inconsistent because many schools are islands and, as such, they are isolated.

This sounds like it’s become a pitch for employing an educational technology strategist however that’s not the point of this post. I’m attempting to paint a generalised picture of schools’ ICT in the UK as over-complex, significantly behind the curve in terms of technology innovation and woefully inauthentic in terms of the experience it provides of the 21st Century digital world we’re trying to prepare our young people to thrive in. I’m suggesting that there should be less ‘complex and expensive’ technology and more ‘simple, fast and exciting’ technology. Schools cannot afford to do everything.

I have already blogged about leading technology and the cloud technology paradigm in education. Both these posts are broadly built around the concept of the 80/20 rule. That is, 80% of the results of any endeavour take 20% of the time and 20% of the cost. The majority of time and money is spent in trying to achieve the last 20%. In practice, most schools and users are utilising their software and hardware at substantially less than 80% by any measure. This means a high level of investment and a low level of utilisation; the worst possible solution.

The reason that the cloud paradigm is rapidly gaining traction in businesses is that businesses are very sensitive to utilisation and efficiency as these directly impact their profitability. The same argument should apply in schools. By increasing utilisation and aiming to deliver solutions that don’t deliver in excess of 80% of requirements, schools will dramatically increase the value they deliver. I worked with a very large number of schools during the UK’s Building Schools for the Future (BSF) programme and one regrettable feature of the project was the waste of money that arose from attempting to reinvent 100% personalised solutions for every project. Schools tend to believe they are all different from each other. In my experience they are 20% different and 80% the same. Recognising this fact drives a different approach to the provision of technology. I respect and enjoy the vocational passion of educators but I do not think that this passion necessarily helps them to make wise investment decisions.

If one aims to meet 80% of a school’s technology requirements for 80% of the time, the optimal technology paradigm will almost certainly shift from the traditional on-premise, client/server model to an out-sourced, centrally hosted (or cloud) model. To date, the evidence seems to support the principle that cloud technology delivers more for less in schools by reducing the on-premise investment in technology (both hardware and people). The rapid advancement in web technology is such that even a pure web model may deliver 80% of a school’s technology requirements without considering other cloud technologies such as thin client and virtualisation. However a Web 2.0 model is almost certainly going to be a more authentic experience for most young people and it is in this sense that cloud technology delivers more for less.

If one aims to meet 80% of a school’s technology requirements for 80% of the time, the optimal technology paradigm will almost certainly shift from the traditional on-premise, client/server model to an out-sourced, centrally hosted (or cloud) model. To date, the evidence seems to support the principle that cloud technology delivers more for less in schools by reducing the on-premise investment in technology (both hardware and people). The rapid advancement in web technology is such that even a pure web model may deliver 80% of a school’s technology requirements without considering other cloud technologies such as thin client and virtualisation. However a Web 2.0 model is almost certainly going to be a more authentic experience for most young people and it is in this sense that cloud technology delivers more for less.

The benefits of moving to a predominantly cloud technology paradigm are outlined below and summarised in the diagram:

- Less day to day management

- Less local infrastructure, resources and energy required

- Quick and easy to deploy, update and scale

- Available on many devices and operating systems

- Available any time, anywhere

- Consistent experience from any learning location

- Stronger links between home and school

- More budget for content, analytics and training

There will of course still be a requirement for investment in on-premise, school technology but only for the delivery of specialist requirements such as CAD or high-end video editing. As with my blog post on mobile, the message for school leaders developing their technology strategy is not: “Everything in the cloud”. It is: “Think cloud first.” The actual answer is almost certainly a hybrid solution but a hybrid that favours a significant proportion of delivery via cloud technology.