I love it when technology does things better, not just differently (or sometimes less well).For the last decade or so I’ve been interested in family history. Not uncommonly for this interest, it emerged with the birth of my daughter. The long journey that had brought her into the world suddenly seemed more relevant to me. So I set about researching my family history and, with my characteristic obsession, soon had a family tree of more than 6,000 connected individuals.

Over the course of this last decade, more and more reference resources have been made available on the Internet, making it easier to conduct research from the comfort of my kitchen table, only venturing out into dusty archives on occasion. One of my favourite resources is Google Books. Google’s mission of digitising the world’s knowledge has already created an invaluable library of digitised, searchable books, many of them historical for reasons of copyright. For a genealogist and a historian, this archive is gold dust (as opposed to the other variety). It’s one thing to know the date of birth, marriage and death for a given individual, it’s quite another to know the individual, who they were and what they did with their lives. Archives like Google Books bring family history alive and I think family history brings history alive by making it relevant.

Before I set out on my family history quest I would characterise my relationship with history as ‘distant’. At school I found the subject dry and uninspiring. Occasionally I would be allowed to pursue project work which I found more engaging. I remember one such project on the Battle of Jutland which interested me because it was a naval battle and my father had been in the Navy. Mostly I couldn’t link these events to my life. Since embarking on the exploration of my family history, I’ve become fascinated with history in all its forms. I can see how it shaped the lives of my ancestors and, in some cases, how my ancestors shaped history. It’s exciting, authentic and personal.

The most amazing thing about these digital resources is that they bring immense power to your fingertips. A decade ago, if I’d wanted to search the contents of a million historical documents I’d have had to employ an army. Today, I can do it by myself in seconds, revealing intimate details about the lives of my ancestors. A recent and fascinating new resource is the British Library Newspaper Archive, offering more than 3.2 million digitised pages, a number growing day by day. In graphic detail, it charts the national, regional and local history of our country, our institutions and our ancestors, opening up the possibility of making history relevant to each and every one of us.

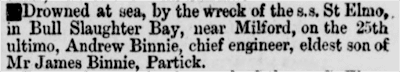

Yes, it is a subscription service, but this is an example of a resource worth its weight in gold (dust), especially when we learn how to mine it (or ‘pan it’ if I’m to stick to the gold dust metaphor). To illustrate my point I’d like to use the example of my 2nd great grandfather, William Smith Binnie. He was a marine engineer, born in Glasgow, who emigrated to Australia in 1876 (by choice rather than at Her Majesty’s pleasure). As a direct ancestor I’ve learned a lot about him. However, he had an elder brother, Andrew, who I’ve never been able to locate. Andrew was in the 1851 census of Scotland aged 14 and then… he disappeared. I assumed he’d emigrated. Within a day of subscribing to the British Library Newspaper Archive, I located the following (and I’m sure they’ll forgive me for reproducing the clip here):

I didn’t intend to end on a poignant note so I won’t. The point is that technology is doing something fabulous here. It is enabling learners (researchers if you will) to access and filter huge volumes of information, vastly increasing the potential to find the points of intersection between the general and the personal. So often it is the relevance of learning to our personal situation that creates engagement. Technology can enable us to do this better.